Western Genre is True America

In an age where we’re told that America is unexceptional, patriotism is down, church attendance has dropped precipitously, and young marrieds are afraid to raise families, the western genre is a very big deal.

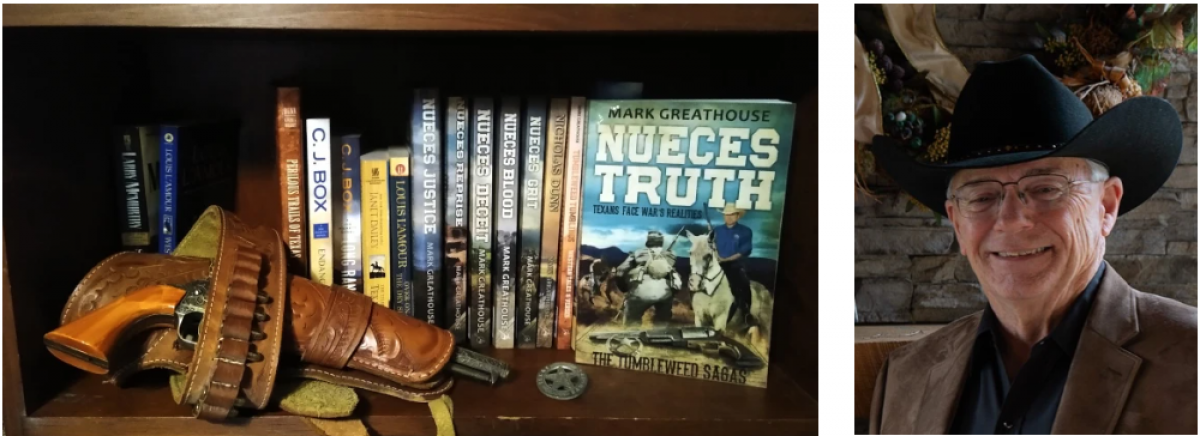

Edgy adventure, tough hombres, and romance set at the close of the War Between the States on the historical Texas frontier of 1864 blaze from the pages of my sixth Tumbleweed Saga, Nueces Truth: Texans Face War’s Realities. It’s more than classic western fare. The characters and the story are fictional, but their personifications existed in the American west even as I’ve worked in actual historical figures of the time. Real events are juxtaposed against a backdrop of rugged but wildly beautiful landscapes. War had swept the nation! Most of Texas’ best men joined the fight, leaving the Texas frontier vulnerable to desperadoes, bandits, and hostile Indians. Luke Dunn’s life is caught up with law and order on the rough and tumble and increasingly war-ravaged prairies of the Nueces Strip while struggling with fundamental moral conflicts and his obligations to wife and family. This reveals an inherent contradiction in terms associated with western genre, not the least of which is its malleability as it’s transitioned from gun fights and good versus evil to more complicated stories. Mingled with the aromas of gunsmoke, leather, trail dust, and bluebonnets are riptides of the forging a life in a rough and tumble world. Plus, western authors are obligated to deliver rapid-fire pacing of action and plot as increasingly demanded by readers in an immediate gratification culture. This adaptation brands western genre as the very backbone of truly American literature, enabling it to endure since its gestation in the early 1800s. It defies credulity that western genre grabs little more than seven percent of readers of fiction. Authors and publishers are left to wonder at what the marketplace is afraid of? Those who blithely toss out. “Oh, I don’t read westerns,” ought to think again, as the genre is ever-inspired to reinvent itself. As to Luke Dunn in Nueces Truth: Texans Face War’s Realities, well, I’ve striven to deliver a character for whom a broader readership might seek. As is traditional with western genre, just about anywhere he rides, death could be reaching for his reins. But Dunn is more complicated. Comanche call him Ghost-Who-Rides, his and young Elisa’s ardor knows no bounds, rogue soldiers pose clear and present dangers, a not-so-civil war rages on, issues of man’s inhumanity to man must be dealt with, savages fight back against their certain demise, and everything converges at Heaven’s Gate Ranch in little Nuecestown, Texas. With Nueces Truth: Texans Face War’s Realities, I invite you to celebrate American exceptionalism, renew your patriotic vibe, rekindle your faith, and rebuild an optimistic view of your future.

Were Old West Cowboys Racist

Whew, I expect it’d be a copout to say it depended on the cowboy, but I’m afraid that’d be the best answer. Mostly, and there were surely exceptions, race simply didn’t matter. Ranching was a huge domestic industry throughout the Old West, and ranchers initially drove small herds to ports and railheads for transport to slaughter houses. Soon enough the Chisum Trail, Shawnee Trail, and other others were blazed by ever-greater herds requiring seasoned cowboys to tend them. Herds were even trailed west through hostile Indian country to the California goldfields. Ranchers like Richard King, C.C. Slaughter, and Charles Goodnight were primarily concerned with getting their beeves fattened up and off to market. They could have cared less about the ethnicity of who slept in the bunkhouse or in a bedroll under the stars. Cowboys were far more concerned with ability than ethnicity. Skin color didn’t matter a hoot, if a cowboy could rope a stray, repair a saddle, brand a yearling, or myriad other tasks. Vaqueros of Mexican descent generally were treasured by American ranch owners. Trail bosses on cattle drives could have cared less whether a cowboy’s skin was white, brown, black, or green so long as they could carry their weight driving beeves through hostile terrain. There were issues with the various indigenous tribes, but so far as the cowboys their concerns had to do with fending off predatory attacks on ranches and on cattle drives. For example, my great great grandfather defended against cattle and horse thievery by Comanche on cattle drives. It was more a clash of cultures than of races. As to how racism translates to today where the horse has often been supplemented by the pickup truck, a cowboy is still a cowboy. And a cowboy’s race still don’t matter none.

Justice in Justice

Most men lead lives of quiet desperation. (Thoreau)

These days, it seems every “minority group” seemingly worth its salt is crying out for justice. I think it’s fitting to kick off my Tumbleweed blog with a free-verse poem I wrote titled “Justice Enslaved.” I hope my readers find it thought provoking. Where indeed is the justice in justice?

To what…to whom are we enslaved? Who forged our chains?

Is enslavement just? Where is the justice? Who decides what is justice?

Slavery justified from the Hammurabi’s Code to Bible scrolls.

Neolithic times segue to Sumer, ancient Egyptian pyramids, Greece,

To China and Hebrew kingdoms, to the ancient Levant…even to the West;

Slavery as punishment, debt repayment, spoils of war, or birthright.

Christian, Hindu, Islam; all find justice enslaved to the law.

Is there justice in slavery? From slavery?

Be it medieval Europe, Vikings, Tartars, or Barbary Pirates;

Slaves were as booty, a mercantile undertaking, a way of life.

Justified in economics essential to the culture, a fact of life!

Whether issued by Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontiex, or Sublimus Dei.

Pope or Imam, King or Sultan…made no matter; misanthropes all!

Justice stood as mute sacrifice to some larger, greater need.

Where then is justice? What indeed is the justice?

Reparation, rehabilitation, retribution…mere slogans.

From Aztecs to Cortez’, Incas of Peru, Comanches of our plains;

To southern cotton fields and tobacco barns enslavement flourished, justice died.

Despite Wilberforce, Newton, and Lincoln, slavery forever prevails.

EBT cards replace chains, urban plantations defy any escape;

Khartoum, Delhi, Jakarta, or Detroit; enslavement abounds.

We cry out for justice. Cry to end enslavement.

Yet its pervasive tentacles imprison all nations, all people;

Justice seems such a shallow game, a losing default setting for life.

What is justice to the enslaved? What then is justice to the enslavers?

And what is justice for those who would end slavery? Such optimistic fools.

Only our souls offer protest, unshackled by iron chains;

Yet justice rings hollow as payment for our past enslavements.

Dare we dwell on justice for past and present sins?

Can money or lives truly compensate for injustice perceived or real?

For justice remains an elusive charade, be it divine or natural,

Be it distributive, egalitarian, social, fair, or utopian.

Retributive and restorative justice stand as inherently unjust;

We find ourselves mired in justice, mine or yours, the red pill or the blue pill;

God forgives, and in the end only “the truth will set you free.”

Indeed, the truth is all that really sets us free; the only justice.